The COVID-19 pandemic has trained the spotlight on supply chains. When the risk of catching a fatal disease is everywhere is there a safe place to source your parts while keeping costs low? Will Stirling, editor at Manufacturing Review, provides his thoughts on the topic.

Supply chains for complex and costly products are always in a state of flux. But massive changes to mature supply chains such as those for the automotive industry are very disruptive and costly. Automotive was already gearing up for life beyond combustion engines, as global OEMs planned to reconfigure factories for hybrid and electric engine models only – the UK is scheduled to ban the sale of diesel and petrol (IEC) engines by 2035, and France and Norway have set similar deadlines.

However, this was expected to be a transformation phased over 20 years or more. These gigantic logistical plans have been hit by COVID but not derailed. Will COVID-19 accelerate the change?

At the moment, sales of new cars are extremely low – the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders says the UK produced just 197 cars in April, a 99.7 percent reduction. With global sales in such paralysis it’s hard and rash to predict if the COVID crisis will change how car components are supplied. There is so much cost invested in the transition from IEC powertrains to hybrid and electric that, with a trickle of revenue, it’s unlikely big OEMS can incur further cost by rushing their electrification plans.

Wuhan, understood to be the source of the outbreak, is China’s automotive manufacturing epicentre. Despite threats to relocate, there is little evidence that global OEMs are closing and relocating their factories away from Wuhan or China in meaningful numbers yet – although India reports growing interest from corporations if not car companies.

“Coronavirus might reinforce an already underlying trend of deglobalisation or regionalisation of supply chains,” says Dr. Steffen Hoffmann, president of Robert Bosch UK. “I would not single out China, as this might affect all countries and regions. It will come at a price and I’m not sure whether consumers would be willing to pay for it. This, plus the complexity of supply chains, in the automotive and other industries will mean that nobody can move quickly. It will happen only very gradually.”

Coronavirus might reinforce an already underlying trend of de-globalisation or regionalisation of supply chains.

steffen hoffmann – bosch uk

Meanwhile, however, battery manufacture is an industry for the future. Not only has Jaguar Land Rover in recent years built a big battery plant at Hams Hall, and Unipart and Williams have the new HyperBat facility in development, but now US all-electric car giant Tesla is looking at the UK for a battery factory.

Property Week reported at the start of June that The Department for International Trade is looking for an initial 4,000,000 square foot site for Tesla to build a research, development and manufacturing plant in the UK, potentially in Somerset.

How have manufacturers in other sectors had to adapt their supply chains to meet the demands of COVID-19?

The production of essential goods such as food, and of course toilet roll, had to increase while some staff self-isolated and social distancing reduced the headcount. A rise in the demand for everyday basics like flour and breakfast cereal put big food companies under pressure, exemplified by the BBC’s ‘Inside the Factory’ documentary, which claimed Britain is eating twice as many baked beans as normal in the lockdown. The Weetabix factory in Burton Latimer has had to work overtime as sales shot up, with more workers eating breakfast at home.

While these peaks will probably level off, home-working is becoming the norm so this bodes well for manufacturers of everyday food that will have to flex shifts. What is the effect on the domestic supply of food and drink?

According to the Department for Energy, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in March, and based on the farm-gate value of unprocessed food in 2018, the UK supplied 53 percent of the food we consume. The leading foreign suppliers of food consumed here are countries from the EU – 28 percent. The UK imports about 70 percent of its fresh produce. For an economy recovering from COVID and with a big trade deficit this represents a huge opportunity.

The Agriculture Bill was introduced to find a system to replace the Common Agricultural Policy, or CAP, which the UK will leave when it exits the European Union. The bill examines many things including food provenance, security and standards. It is an opportunity for the farming industry to lobby for greater investment in food production, labour solutions, technology in the field and the factory, and greater self-sufficiency. We only grow 30 percent of the fresh produce – vegetables and fruit – we consume, and we don’t eat enough of this healthy food in any case, according to the British Growers Association.

First Brexit and now COVID-19 have put huge pressure on labour in both fresh produce picking and packing, and food processing and manufacturing, which traditionally relies largely on labour from eastern Europe. Experts think there will be an employment shift and growing and processing will employ more British workers, but it must be coupled on the arable side by digital technology and ‘precision farming’. Conventional harvesting practices – huge tractors and combines – are unsustainable because the very heavy machinery compacts and degrades the soil. Progress in this area could become a new industry for Britain, exporting agricultural robots and smaller, autonomous tractors that work in ‘swarms’, currently being proven by researchers at Harper Adams University.

In May the Financial Times reported that one of the big outcomes of COVID will be greater adoption of automation in the food industry. Traditionally food manufacturing has had much lower robot investment than automotive, both in absolute terms but also considering its size as the biggest manufacturing sub-sector. Food companies are expected to invest in automation and robots in the medium term, post-COVID recovery, as margin pressure and social distancing measures bite.

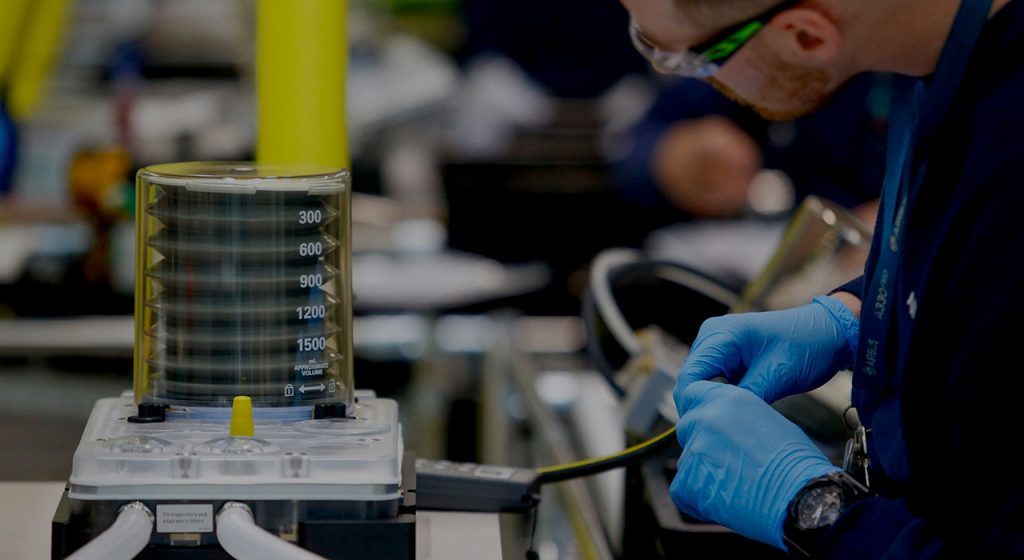

COVID-19 has tested the flexibility of big companies to the limit. Several large engineering companies like Airbus, GKN, and Renishaw got together and formed The Ventilator Challenge, to make thousands more Penlon and Smiths Medical ventilators to a proven design. These firms had to ‘pivot’ at short notice to make new components with brand new tooling and processes hitherto untested in their factories and in record time. Their suppliers pivoted too. Many small and medium-sized engineering firms had to use new tooling and change shift patterns, sometimes after furloughing staff, to make the new components needed by these ventilator consortia.

What does this prove for supply chains? It showed that big companies, often seen as inert and slow, can respond very quickly if they are forced to, collaborate with their competitors smoothly, reconfigure millions of pounds worth of tooling and make something complicated from scratch in weeks.

Maybe this is a real case study for ‘Industry 4.0’ – not the futuristic ‘cyber physical systems’ we think of, but the agility of rapid response manufacturing capability and industry collaboration.

Future industries

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed the frailty of both the UK’s standard bearer industries, aerospace and automotive. Neither will ever be the same, because even when volumes recover the powertrain technology used to propel these vehicles has to change. When aerospace recovers, some say between four and eight years, there will be fewer wide-body and jumbo class aircraft and greater demand for single aisle planes with efficient engines and light, composite frames that can fly as far as possible on a tank.

The UK needs to start investing in a programme of research and development to support the next generation of manufacturing production technologies

jane godsell – university of warwick

With the ‘industrial strategy’ coming back onto the table, even quietly, Britain must think about what it’s going to make for the next 20, or even 40 years – although calls for a lasting long-term industrial strategy have fallen on deaf ears in the past. Professor Janet Godsell at University of Warwick says Britain needs more resilient supply chains: “The UK needs to strategically review the products that are critical to life and ensure that there is the capability to produce these domestically, with the ability to ramp up volume if required.”

She advocates making more advanced machines that make things; our machine building industry is tiny and Britain has no domestic robot manufacturer of scale. “As we move into the post-COVID-19 era, the UK needs to start investing in a programme of research and development to support the next generation of manufacturing production technologies and identify opportunities for new emerging technologies where we may be able to ‘leapfrog’ the competition, where a longer-term investment plan is critical to long term success”, said Godsell.

A ‘one to watch’ sector for British supply chains is renewable energy. Greenpeace is campaigning for a green economic recovery, and this year 10 percent of all our electricity was generated by offshore wind with more to come. RenewableUK, the business group for the renewable energy industry, says 58 percent of entire lifetime UK offshore wind farm content comes from the UK. It has a programme of supply chain events (digital and in-person in 2021) and its November 2019 report says UK-based onshore and offshore wind, wave and tidal energy companies are now exporting their products and services to 37 countries across six continents. ‘Export Nation’ (a report by RenewalableUK) shows that 47 UK firms signed 465 contracts worth up to £53m per company in the past year.

If government policy continues to back both offshore and onshore (more difficult) wind farms, we should see the UK-made content proportion rise, creating more jobs and potentially exports.

While COVID is destroying GDP and jobs this year, it is giving the UK a unique albeit desperate opportunity to change what we make, where we source parts from, to consider the environment more, make locally and accelerate digitalisation.