The inside story of how a group of rival companies came together to make ventilators for the NHS during the COVID-19 pandemic

Andrew Trotman, Head of News UK

6 July, 2020

It takes a lot to surprise Mark Mathieson and Graham Hoare these days. They have a calmness and confidence in their work that’s been honed over many years of leading some of the most innovative teams at two of the world’s top automotive and motorsport businesses.

Mathieson, Lead Partner for Technical Services at McLaren Racing, and Hoare, Executive Director of Business Transformation and Chairman at Ford, have the experience to always see the big picture. They are the cool heads in a crisis.

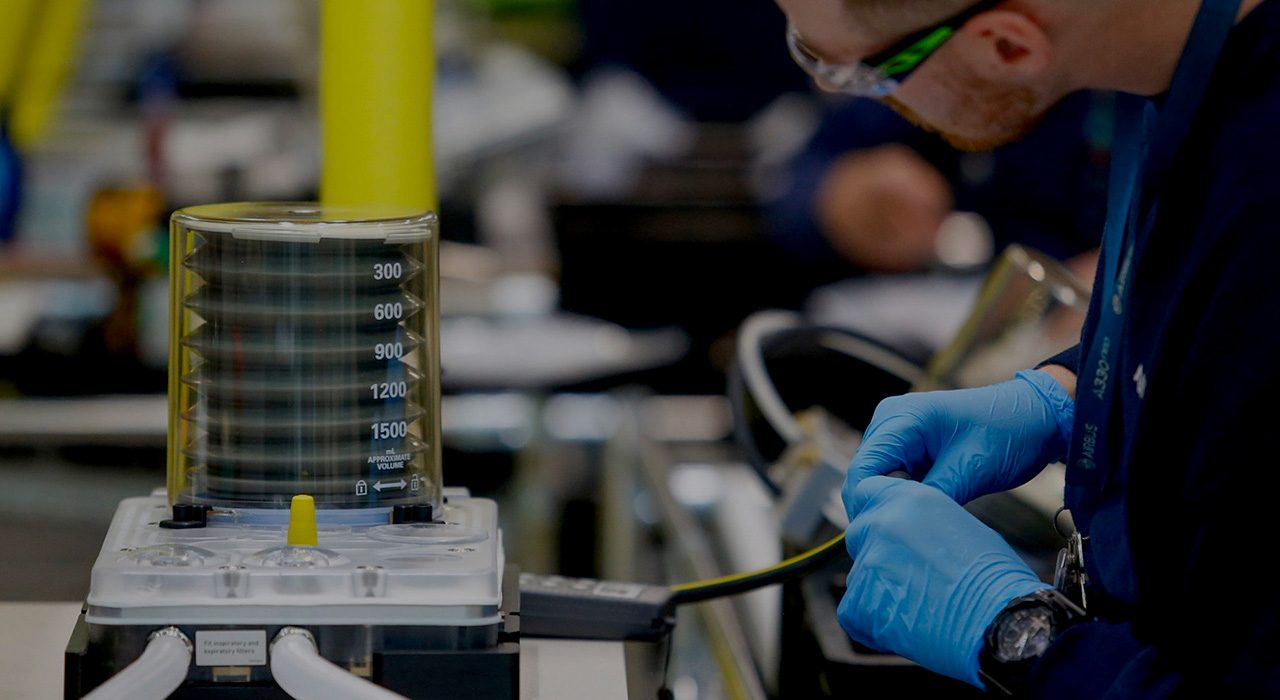

These two men played key roles in a unique group that was asked to produce ventilators, when the UK urgently needed up to 15,000 of them to save lives during the Coronavirus pandemic.

“On the production side, we are building 400 ventilators a day. What would normally take six months was taking a day. We achieved over 20 years of normal production in just 12 weeks,” Mathieson says. There’s a pause on the Microsoft Teams call, as if he is still trying to get his head around the scale of what he’s been involved in over the past few months.

Some of the leading companies in the world, including Ford, McLaren, Unilever, BAE, GKN Aerospace, Rolls-Royce, Unilever and Airbus, changed their businesses overnight and came together to build ventilators for the NHS. They were working on two designs – one from SmithsGroup, the other from Penlon.

It was an unprecedented project; one that required more than 30 of the UK’s biggest companies, the best minds and the latest, cutting-edge technology.

Leila Martine, Product Marketing Director for Mixed Reality at Microsoft, said: “We knew that Microsoft technology could potentially help and support the incredible work that this UK consortium was delivering for the UK. We worked alongside some of our partners, including Accenture, Avanade, PTC, Zenzero and Content and Cloud, to ensure rapid deployment of Microsoft HoloLens, the Azure cloud platform, Teams, Dynamics 365 and Power BI to the consortium.”

Each of these tools played a critical role as the consortium ordered parts to build the ventilators, construct them at sites across the country and send them to the frontlines of the NHS. HoloLens, Microsoft’s mixed-reality headset, allowed assembly line staff to see holograms of how parts fitted together and make hands-free video calls to experts while they were working – a feature called Dynamics 365 Remote Assist. Just by using voice commands and hand gestures, they could bring up a virtual screen that hovered in front of them, displaying a live stream of someone with knowledge of the ventilators, wherever they were in the world.

That was critical for 2,500 engineers who had spent their careers building products such as cars but now had to switch to assembling medical equipment overnight.

“HoloLens has enabled this project to be successful. I would say that without it, we would not have achieved the objectives that we’ve achieved,” Hoare says. “For our team in Dagenham, HoloLens became this direct bridge to Penlon [the ventilator’s designer] in Oxfordshire. It changed a situation from one that was extremely complicated to envisage to one that was far more tangible and reachable. It inspired the Ford team. They picked up HoloLens and it was so easy to use; it became second nature to them.”

Mathieson agrees, adding that teams “were pretty blown away [by HoloLens] and wanted to use it more”.

Every piece of technology had to be simple to use for the members of VentilatorChallengeUK because time was constantly against them. Every day in the UK, thousands of people were catching Coronavirus and hundreds were dying.

Avanade, a Microsoft partner, helped the consortium set up the technology, building a Dynamics 365 Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system in two weeks that could manage all the parts, ship them and bill them. “This project was a showcase of speed, acceleration and breaking with tradition, combined with thinking a bit differently,” says Chris Bingham, the Lead on Avanade’s VentilatorChallengeUK work.

While speed was important, the finished products also had to be perfectly made in line with strict specifications set by clinicians and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

To help the consortium, Avanade called on teams from around the world to create a network of support that ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The company worked with Microsoft and Accenture to create a supply chain for components to be bought, tracked and paid for. Avanade also built a “control tower” dashboard that gave one source of truth for all the companies involved in the consortium.

Stuart Lee runs the Azure centre of excellence for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Avanade. “We ensured that someone who didn’t know what HoloLens was could just pick it up and turn it on, and it did what it needed to do,” he says. “If anyone needed help we had resources in the UK, Germany, Holland, New York, Seattle, Florida, Washington and Toronto in Canada. All these teams in different countries were focused on helping the UK make ventilators for the NHS. Everyone wanted to help because they felt it might be their family or someone they cared about that might need one of these ventilators.”

As part of the training workstream, Microsoft and its partners were key to building mixed reality training tools that would be deployed rapidly. Martine pointed out that “PTC played a vital role within the consortium with their Vuforia Expert Capture app. The ability to move from paper-based instructions to provide digital step-by-step instructions that could be viewed on a mobile or tablet form factor, has been important to sharing knowledge quickly.”

That was not only crucial for the people on the assembly lines, going through 190 separate steps to build a ventilator. It was also important for managers on the project, who had to ensure the assembly lines were efficient, staff were kept safe, the right parts were ordered and sent to the right place at the right time, and completed ventilators reached the frontlines of the NHS.

Some of the companies in VentilatorChallengeUK were used to buying five or six components at a time, and they were now being tasked with purchasing up to 30,000.

There was another major issue. With the Government announcing strict measures to control the spread of Coronavirus, the initial stages of the project had to be organised and run by senior staff from the consortium’s 33 principle companies without them ever meeting in person. “We’ve been working together for weeks and I’ve not met any of my colleagues face to face, but they probably know me better than my wife does by now,” Hoare says as he laughs. “It’s so bizarre.”

Communication and decision-making based on accurate data were key.

“The project was enabled by Microsoft Teams,” Hoare adds. “So not only did we have an environment where we could communicate, but we could draw data, as well as displaying it in Power BI and sharing it via Teams. Basically, it was easier to use data than not use data.”

Of course, car companies such as Ford and McLaren are used to placing data at the centre of their operations – everything from aerodynamics and materials to personalisation for the customer is all based on information. The difference with the VentilatorChallengeUK was that data had to be gathered and used in minutes and hours instead of months and years.

“One key area has been having data and forming decisions appropriately,” says Mathieson at McLaren Racing. “We actually started with very little data and used our experience to formulate how we should build the project. As we’ve grown through the programme, we’ve been focused on getting more and more data into that decision-making process. As a consequence, we’ve been way more effective with our decisions and pre-empting some of the challenges that we’re going to have.

“In a programme like this, you don’t really have very much time to deal with things, so if you can be pre-emptive, then it has a massive benefit.”

Mathieson gave an example of how nimble the consortium had to be in its early days. The pandemic forced organisers of the Australian Grand Prix to cancel the race just a couple of days before it was due to be held in Melbourne on March 15. McLaren shipped its F1 cars back to its headquarters in Woking, Surrey, where they are usually tweaked and refined, ready for the next race. This time, the cutting-edge vehicles, which cost millions of pounds to design and build, were pushed to the edge of McLaren’s build bay and covered up, so engineers could create space to build the trolleys that the ventilators sit on. Sport didn’t matter when lives were at stake.

With F1 on hold, the team focused on building as many ventilator parts as they could. “There were trolleys everywhere – on the main boulevard at the McLaren Technology Centre, in trailers at RAF Odiham and Farnborough. We spoke to Goodwood Racecourse and they kindly let us store ventilators underneath the grandstands. I think we had about 5,000 trolleys there at one point,” Mathieson says.

The VentilatorChallengeUK consortium, working day and night, has undoubtedly saves lives during one of the most uncertain and dangerous periods in modern history. But while the lockdown is beginning to end, the consortium’s work is not. In May, Dick Elsey, Chief Executive of the High Value Manufacturing Catapult and Chairman of VentilatorChallengeUK, marked two months of the consortium by saying: “Although the UK is widely accepted to have passed the peak of infections in this first phase of the pandemic, we are continuing to scale up our production capabilities to make sure that there is always a ventilator available when a patient needs it should a second wave strike the UK. I look forward to seeing VentilatorChallengeUK deliver even more ventilators over the coming weeks.”

Every member of the consortium is currently focused on saving lives, but I asked Mathieson and Hoare whether the project would change how McLaren and Ford worked in the future. Will the levels of speed, agility and focus they were forced to adopt be transferred to their own operations?

“Very simply, this is how we need to operate going forward,” Mathieson says. “The auto industry –and it’s true of many other sectors as well – will have to embrace a lot of change, and a lot of that will be focused around technology and culture. This has been a fantastic example of what can be achieved if you get rid of all the normal obstacles, have a clear, laser-sharp focus on the objective, and then people just come together to make it happen.

“Remote working has really come to the fore, and now companies are looking at the future and thinking ‘what space do we need and how do we operate our teams’.”

Hoare believes HoloLens will continue to have a major impact at Ford.

“When you use technology like HoloLens, all of a sudden the rest of your world starts to change shape,” he says. “We can certainly think of applications for the headset in the automotive world. This technology will set us free, reducing our carbon footprint through reducing the amount our staff have to travel. When we need an answer to a very specific problem, we often end up saying, ‘We need Fred on the plane’, and Fred will fly from Asia to the UK to help solve the problem. Then we realise it actually wasn’t Fred we needed, it was Barry who has the skills we need, so he flies over on a plane. There is tremendous potential for HoloLens there.

“It will be one of the memories I take away from the consortium: how the right tools in the right hands with the right need makes all the difference.”

The companies involved in the consortium include:

- Airbus

- BAE Systems

- Ford

- GKN Aerospace

- High Value Manufacturing Catapult

- Inspiration Healthcare

- Meggitt

- Penlon

- Renishaw

- Rolls-Royce

- Siemens

- Smiths Group

- Thales

- Ultra Electronics

- Unilever

- UK-based F1 teams Haas F1, McLaren, Mercedes, Red Bull Racing, Racing Point, Renault Sport Racing and Williams

Enablers of the consortium include:

- Arrow Electronics

- Accenture

- Avanade

- Dell Electronics

- Microsoft

- PTC